(Adapted from a homily for the feast of Saint Thomas.)

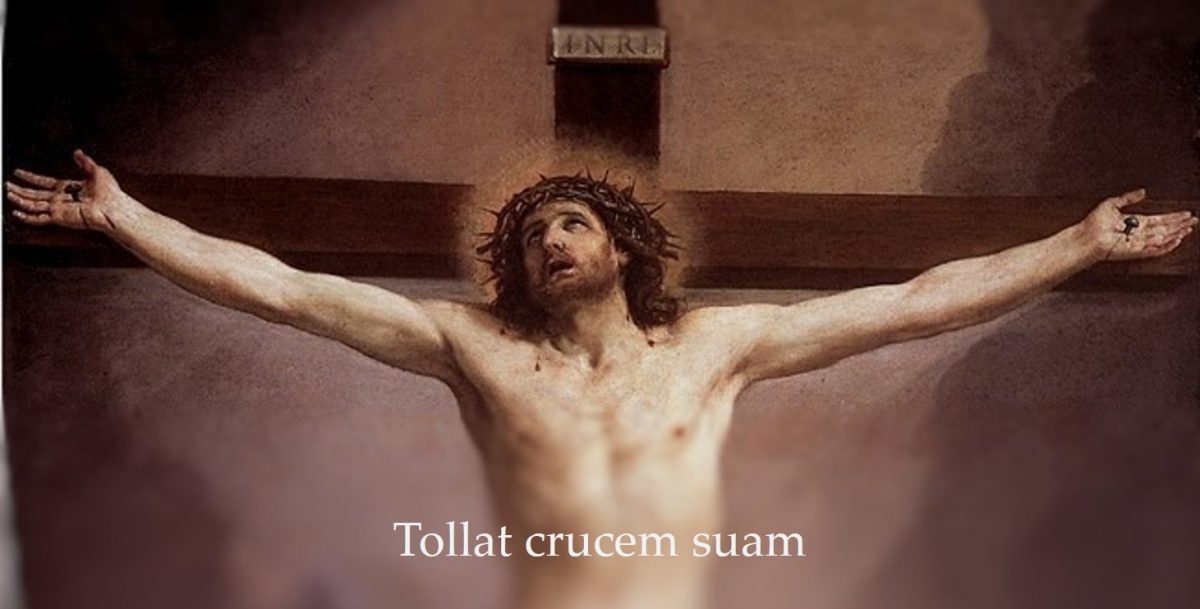

“Unless I see the mark of the nails in His hands and put my finger into the nailmarks and put my hand into His side, I will not believe.” With such words, Thomas the Apostle states his position on the re-appearance of Jesus, His Master, whom he had followed from Galilee to Jerusalem and death. And while Thomas is often described as “the doubter”, his condition for belief teaches us something important about the faith we share with him: it is incarnational. Our faith in God is not a matter of “pure spirit”: it is faith in the God-made-man, Jesus of Nazareth. It is not a matter of small or accidental importance that we believe in “Jesus Christ”, as our Creeds give us to say. Our belief is not in an invisible God, but in a God who came down to earth, who became truly one of us in order to save us. This Jesus, a man among men, is in fact the Son of God. But He is the Son of God made man, and it is the Incarnation that is the pivot point of history and the crux of our faith.

“The Son of God became a son of man so that man might become a son of God.” (To quote Saint Irenaeus, another saint whose feast falls today.) The Incarnation is essential for our Christian faith, because it is essential for our salvation. It was by the Incarnation that human nature was restored to its original dignity, and indeed elevated infinitely beyond that original dignity, for in being joined to the Divine Son, human nature is raised above even the angels. That human nature which the Son of God assumed at His Incarnation was the very nature by which He was able to undergo death for our salvation–God can’t die, but God-made-man can. And it was only because God had a body that God could have a bodily resurrection, of which resurrection Saint Paul says, “If Christ is not risen, your faith is in vain.” It is the Body of Christ that He gives us as food in the Eucharist, so that we Christians might be grafted into His Body and receive adoption as sons, so that we might truly become what we eat. The Body of Christ is essential to our faith.

And besides, it’s not surprising that Thomas wanted to be a member of the same cohort as the rest of the Apostles, to whom Christ “showed His hands and His side” on the evening of Resurrection Sunday, while Thomas was absent. Christ had granted a token of apostleship to the others, and Thomas earnestly desired to be counted in that number. Christ founded His Church upon an apostolic college that had truly witnessed the resurrection, and they would need this witness in order to bear that witness to the world. Thomas–the one who had urged the others to join him in going back to Judea with Jesus “to die with him” (John 11:16)–did not want to be “left out” of that apostolic band, and he knew exactly what was necessary in order to exercise his ministry. In yearning for the physical encounter with Jesus, he demonstrated the necessity of Jesus’ physical resurrection for His apostolic commission. Thomas wanted to be one of the Twelve after the Resurrection, as he had been before. As he had wanted to be united to Christ in death, so also he wanted to be united to Christ in resurrection from the dead.

The physical reality of the object of our faith–Christ’s physical and resurrected Body–shows us that the observance of our faith must also be physical. Jesus used his Body to offer perfect worship to God, and the Apostles understood that they were to imitate that mode of worship. “Present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God,” urges Saint Paul. Indeed, our physical offering “is [our] spiritual worship.” The body and the soul are not two distinct realities, but a single whole, by which we join our whole selves to God. This is why authentic Christian worship is physical as well as “spiritual”. This is why we gather as an assembly for Mass, and why we use deliberate postures in our prayer. This is also why the Christian faith has always held the physical creation to be fundamentally good. God created it! And that means that things like alcohol, food, and sex are good! We use wine in order to consecrate the Eucharist, and marriage is a sacrament! But these things are good inasmuch as we offer them as sacrifice to God, inasmuch as we use them for the purpose God intended. The converse of the principle that physical things matter for good when we direct them to the proper worship of God is that they also matter for evil when we abuse them. This is obvious in the abuses of drunkenness and gluttony and lascivious sexual behavior. But it holds true for every created physical thing. And since the Fall has produced disorder in our physical desires, we do well to worship God by offering Him our bodily mortifications. We abstain from meat on Fridays in honor of Christ’s death. We fast. We deny ourselves physical pleasures and willingly endure physical discomfort as an offering to God of our whole selves. Indeed, the mode of the Christian life must be patterned on the martyrs, who offered their whole lives to God in sacrifice, in imitation of their Divine Head. The Apostles teach us this lesson from the very beginning. And the lesson begins from the encounter with the truly-risen Christ in the Upper Room.

And yet, the lesson Thomas teaches is not complete. When Jesus does appear to him and draws him into the encounter he so desires, he demonstrates true faith. For faith is placed in that which is not seen. Faith is in what is not physical. “My Lord and my God!” Thomas saw the body, and he confessed the divinity. He believed in what he could not see, and for that, he serves also as the model for our faith. For we who have not even seen Christ’s Body (except under the veiled signs of the holy Eucharist) are indeed included in His blessing. We too confess Him as Lord and God, who have believed in the testimony of His witnesses. And we need have no fear of being relegated to some lower rank in God’s kingdom just because we happened not to be present in first-century Judea. We are blessed by Christ with the same faith as the Apostles held. We believe what the Apostles believed, and for the same motive: Jesus Christ, the God-man, has demonstrated His power on earth, and we have believed that He is indeed “the Christ, the Son of the Living God.”

(I gratefully acknowledge catholicexchange.com, whose site hosted a reflection on Saint Thomas’ faith that spurred some of my own thoughts in this post.)